Mission: To promote driving less so all may live more.

This web site promotes self propulsion above all forms of transportation. Other forms of transportation should of course be considered as an advancement. However, an advancement doesn’t entail perfection.

Before we consider kick scooters, take electric cars, for example: they may be potentially fossil fuel free, but any plastics in their design are likely petroleum products and, currently, natural gas (a fossil fuel) provides the electricity for the bulk of electric cars in California, a forward-thinking state that admits humans have a pollution problem.[1] In addition, electric cars may involve manufacturing pollution[2] and disposal pollution[3]—as well as human rights abuses.[4]

Eventually, I assume, the gas/diesel powered car will become a museum piece, not that electric cars address the primary concerns of Person vs. Automobile: they still impinge upon the environment, menace people and animals, and make annoying tire noise at highway speeds.

Onto the Kick Scooter

On one hand, electric scooters address all the negative aspects presented by electric cars: they don’t make annoying highway-speed tire noise (rarely reaching highway speeds, as well as lacking the mass and surface area to generate much noise); the materials required for manufacturing and disposal are markedly less than for automobiles. Furthermore, although we will look at collisions with pedestrians, as a pedestrian, I’d sooner be hit by a scooter than an SUV any day.

On the other hand, scooters have established a gnarly reputation at best. One hears of homicidal and suicidal driving habits, as well as rivers and lakes being polluted by scooters that make their home in these watery beds. Rules are unclear. Helmets? Sidewalks? Streets? Gutters? Some jurisdictions require them to avoid streets, while others insist they use the streets. In Ireland one cannot insure them, but the police reportedly confiscate them precisely because they are not insured.[5]

Scooters make bicycles appear as a well-accepted form of American transportation (and anyone who rides a bike knows that isn’t true).

In an extensive interview, I asked four people about their experience riding scooters. Three of them said it simply felt dangerous, one of whom rode for less than a minute before returning to ambulation. These three were millennials. The fourth person was a grandfather. He said that where he rented one (at a touristy waterfront), helmets were both legally required and unavailable. But the clerk did hand him a piece of paper with the name of a company that would take a mail order for a helmet.

Between 2014 and 2018, among millennials, injuries on micro-mobility devices increased nine-fold. “One quarter of injuries included a broken bone and one-third of injuries were to the head, double the rate among bicyclists. A separate 2019 study found less than 5% of e-scooter riders wear helmets” (“Electric scooter injuries tripled in one year among US millennials, study finds”, Guardian, January 8, 2020).

Companies such as Lime and Bird have injected electric kick scooters into major cities with the result that by downloading a smartphone app and (I assume) including a credit card number, users can rent a scooter and, in a matter of seconds, be riding a low-polluting vehicle. At the same time, they may be endangering the lives of pedestrians and other scooterists, as well as bicyclists. Finally, after the scooter gets parked wherever its driver needed to go, the scooter may be picked up by a disgruntled citizen and tossed into a river, lake, or ocean.[6]

As Carlton Reid notes in his book Roads Were Not Built for Cars, bicycles had an uneasy reception, endangering and aggravating pedestrians as scooters currently do. Lobbyists and the sheer elegance of the bicycle won the day (for the most part). The history of bicycles demonstrates that a form of transportation that initially threatens the public may find eventual acceptance. Whereas bicyclists were first considered the aggressors who endangered pedestrians, now they are more commonly the victims, assaulted by careless and belligerent automobile drivers.[7]

Not every technically sweet form of transportation makes the transition though. As Reid points out, in spite of its capabilities, the Segway encountered many difficulties as it entered the market. The price ($3,000-$6,000) was a deterrent. Worse, cities provided no infrastructure for these vehicles. They were fit neither for sidewalks nor streets. As it has turned out, they remain popular as service vehicles for policemen, security guards, and medical personnel (i.e. those who can do what they want), but not for the consumer.[8] As Jordan Golson remarks in an article in Wired: “No, the problems that sank the Segway weren’t technological. They were social.”[9]

Photo by Reinhold Eder, posted on Wikipedia

Photo by Reinhold Eder, posted on Wikipedia

It is easy to see how kick scooters have circumvented the problems encountered by the Segway: they are rented, not owned. Moreover, they have been injected into some cities in such great numbers that it is a matter of asking forgiveness, not permission when it comes to riding them. The smart phone, no doubt, has been indispensable in assisting their popularity.

What, one wonders, is the net effect of electric kick scooters on society? Are they completing the transportation line, picking up riders where trains and buses leave off? Is there one documented case where the use of an electric scooter supplanted the use of an automobile? Are they primarily an alluring substitute for a healthy walk or bike ride—with the added disadvantage of ending up in and polluting urban waterways? The people who throw these vehicles into rivers, lakes, and oceans—are these people concerned that the scooters are cluttering sidewalks, sometimes parked carelessly (which still doesn’t explain cluttering waterways), or are they, dare we say, envious that for one reason or another they cannot join in the fun (low fear threshold, no smart phone, bad balance)?

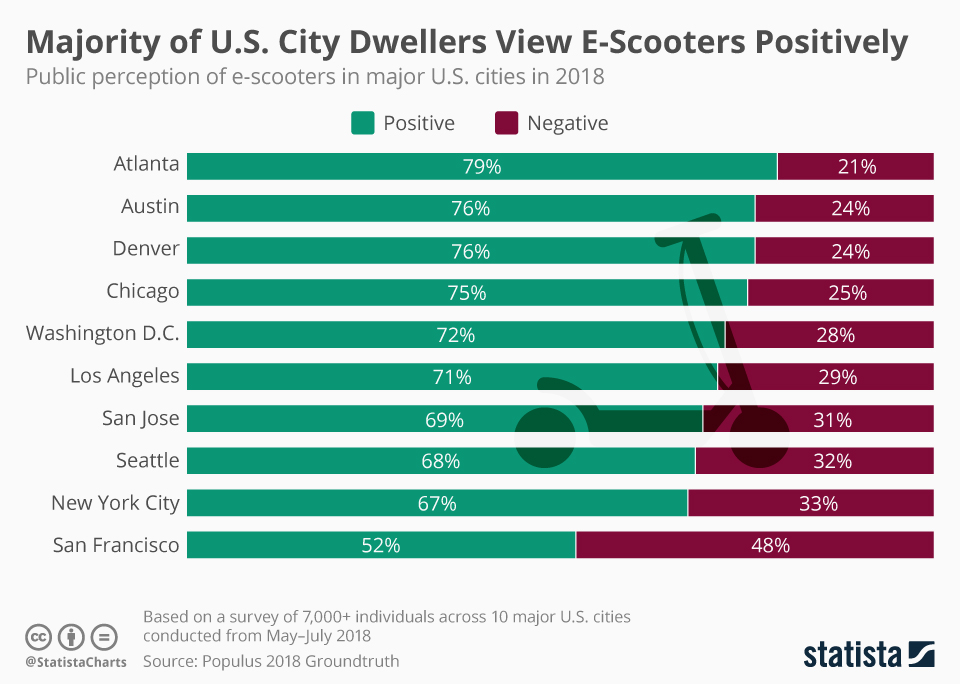

The answers to these questions elude me. I’m new to the business. Part 2 of 2 of this investigation will involve my first (and probably last) ride on a scooter. As the reflections on the history of the bicycle suggest, the jury is still out on the role of kick scooters in urban areas. But, judging by the 2018 data graphed below, my bet is that with increased regulation, along with scooter vandals being fined stiffly, scooters will become respected as a relatively innocent form of urban transportation. After writing the previous sentence, I bought some kick scooter stock—just to make good on my prediction.[10]

Applying the popularity test among US cities, scooters get a net win, as this graph from statistic illustrates (2018):

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

____Footnotes____

[1] “Electric Cars Mostly Run On Electricity From Renewable Energy Or Natural Gas”, February 6, 2018.

[2] The production of electric cars—as a result of their massive batteries—may increase the greenhouse footprint 15% above producing gasoline cars. “Electric cars may be the future, but they’re still critically flawed in a key area”, February 6th, 2018. This view is challenged, however, by an article on Forbes.com: “Are Electric Vehicles Really Better For The Environment?”, May 20, 2019.

[3] This review article in Nature provides a hierarchy of preferred responses to the problem of both creating and disposing of lithium batteries. The goal is to reuse as much of the battery as possible, which action addresses both manufacturing and disposing issues.“Recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles”, November, 6, 2019.

[4] “The dirty secret of electric vehicles”, March, 27, 2019.

[5] “Motorized scooter”, Wikipedia, last updated January, 21, 2020.

[6] All these points, as well as a discussion of the reception of bicycles, is mentioned in this excellent article: “What the Fight Over Scooters Has in Common With the 19th-Century Battle Over Bicycles”, December, 2019.

[7] I appreciate the reminder of Reid’s work provided by the aforesaid Smithsonian article: “What the Fight Over Scooters Has in Common With the 19th-Century Battle Over Bicycles”, December, 2019.

[8] Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How Cyclists Were the First to Push for Good Roads & Became the Pioneers of Motoring, by Carlton Reid, 2015

[9] “Well, That Didn’t Work: The Segway Is a Technological Marvel. Too Bad It Doesn’t Make Any Sense”, Wired, last updated January, 16, 2015.

[10]As it turned out, I couldn’t find a publicly traded company, so I bought three shares of Lyft stock instead, since they now rent scooters.