Mission: To promote driving less so all may live more.

[Don Bushey, owner of Wilderness Exchange and, along those lines, quite active in rock climbing and skiing, wrote the following in an email.]

I honestly think that recreational road riding is the most dangerous activity I engage in—at least statistically this seems true. The main difference is that with the other dangerous things I do—rock climbing, backcountry skiing, and surfing—there are behaviors and actions that can minimize and reduce my risk. With road biking, it is entirely out of my control (except for wiping out), and getting hit by a car from behind is a purely objective danger. I should tell you sometime about my near death experience that I had on a road bike up Sunshine Canyon . . .

[So I asked for more, getting the account along with his theory of risk ~ Louis]

Near Death in Sunshine Canyon

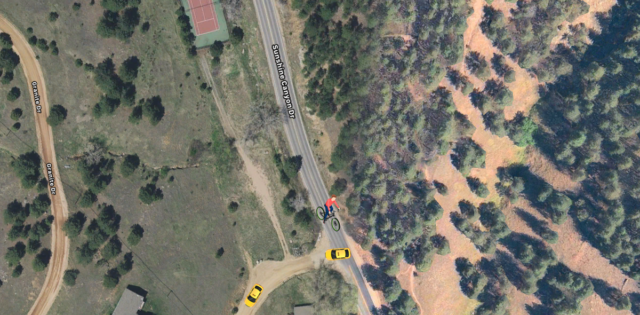

One cool crisp Fall evening about eight years ago, with the light reddening through the slot of Sunshine Canyon, I reached the end of the climb up Poorman’s on my road bike and pointed my front wheel down the steep [Sunshine Canyon Drive], winding through the canyon.

This is where the thrill lies with road biking—the stoke—the rush. I took a deep breath and performed a little self-assessment, as I always do when embarking on an experience like this. Do I feel balanced? Strong? Relaxed? Are there anxieties and apprehensions? If so, are they real or imagined? This will determine the speed and commitment level I am willing to give to the descent. I exhaled and realized that I was tuned in and feeling great. I launched into the descent and quickly gained speed and velocity.

I love this [particular] downhill because there is such light vehicular traffic, and the grade and the angle of turning are perfect—allowing the rider to push speeds as fast as a bicycle can travel (~50 mph) with only one mandatory switchback to brake.

I quickly gained full cruising speed, feeling my sweet Italian handcrafted steel frame flexing and carving beneath me. I felt like I was flying!

You try to zone in and out, gaining a new hyper-awareness of your surroundings; your visual perspective increases, and you begin operating from an intuitive place, rather than an analytical one. Do the movement of bushes on the roadsides indicate a deer hazard? Does the rustling of leaves in the trees suggest a breeze that you may need to counter? Is that water on the road or a mirage? What are the options and ways out if so?

In this hyper-aware state, I saw a car several hundred yards down the canyon making a left turn on Timber Trail, directly in my path of travel. They saw me, and completed their turn (meaning they got out of my lane and were now headed up their dirt road), so I continued on, without needing to brake.

The very next moment, now only a couple dozen yards from that intersection, a second car sped up and initiated the same left turn.

This can’t be happening!

In a split second, my awareness changed from enjoying the thrill of a recreational road ride, to facing an almost certain head-on collision with a car at full speed. I vividly remember seeing myself from above, like I was watching a movie. I was not in my body anymore. Operating on some form of primal intuition which I’ve never before or since been able to access, I saw myself turn into the lane of oncoming traffic, bearing down on my front wheel, initiating the deepest and fastest carve (as we skiers say) and immediate deceleration I have ever achieved on a bicycle.

I miraculously stayed on the bike and did not lay it down. Fortunately, there were no other oncoming cars. Still mounted on my bike, I slowly came back down to earth, body coursing and shaking with adrenaline and endorphins. Pulling over, I buried my face in my palms, weeping uncontrollably.

Death on Lookout Mountain

Several years after this incident, my friend Tom was killed on a similar descent down Lookout Mountain in Golden. A car swerved into his lane, ending his life, while leaving behind a widow and a son. Road biking is like Alpine climbing—so full of objective dangers. It’s guilty of subterfuge—an objective danger fox dressed in subjective sheeps’ wool. The actuary rate far exceeds the 8 in 1 million chance I have of dying rock climbing. Person vs. Automobile? Auto wins every time. It’s the most dangerous damned thing I do. But I love cycling and wouldn’t give it up for anything.

Why Don Rides Again and Again

-Thomas Jefferson

“Except when road biking”

-Don

Bicycles are perhaps one of the greatest inventions of all mankind, except for the wheel, of course, which was only a small step forward in the invention of the bicycle. It’s hard to imagine a more direct union of human and machine—the stuff of dreams and imagination.

They allow us to become faster than we are; we soar, we carve and bank into turns, experience g-forces, exhilaration, acceleration, and an overall sense of fun and well-being—all generated by gravity and our own power.

Riding bicycles—whether engaged in recreation or transportation—is a risky proposition. The outcomes of interactions with cars have been sadly topical on this blog, and, leaving cars in their garages, the possible outcomes of mountain biking at 40 mph down steep forested trails over rocky mountainsides are obvious. Acceptance of risk is highly individual, and our relationship with risk is at play with almost every decision we make; in a way, it shapes the way that we express ourselves in the world.

Outdoor adventure sports like climbing, backcountry skiing, and surfing have informed and shaped my relationship with risk in almost every way—except, perhaps, running a business, which is ten times scarier than any of these sports.

But recreational road biking is not one of these activities where the Jeffersonian risk-reward ratio quite meters out.

Road biking is rife with objective risks, as I conclude with references to mountaineering and climbing. Subjective risks are risks that can be mitigated by an individuals’ judgement, behaviors, and decision making. Objective risks are risks out of an individual’s control. In Alpine climbing, which takes place in remote high mountain areas, objective risks like rockfall, icefall, lightning strikes, and avalanches, although mitigable, are an accepted part of the game. In sport climbing, where there are fixed anchors and a controlled environment, there are almost never objective dangers, and with proper use of equipment, the accepted risks are perhaps a sprained ankle, or an overuse injury. Tragedies in this environment almost always involve human error. Every climber quickly comes to a place where they are comfortable with their level of risk, decides what is acceptable and not acceptable, and works at exercising good judgement to ensure a long career.

None of this explains why I continue to ride my road bike. As I said, “acceptance of risk is highly individual.”