Mission: To promote driving less so all may live more.

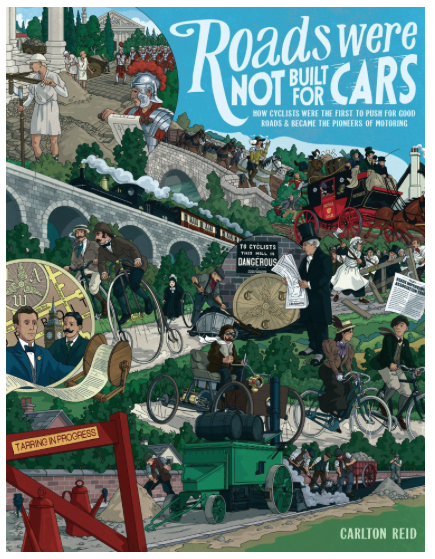

Accordingly, this post (continued in Part 2) will recapitulate some key points from the book Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How Cyclists Were the First to Push for Good Roads & Became the Pioneers of Motoring, by Carlton Reid, 2015.[1]

This book gives the lie to the common history that the automobile—that vehicle that has taken over much of the world—made its entrance initially as a “horseless carriage.” Far from it, at least in England and America, the regions for this study. The automobile evolved, both mechanically and politically, from the bicycling industry. It was the bike clubs that initially lobbied for “Good Roads,” even while they were moving from solid to pneumatic tires.

Bicycles promised to emancipate people. For example, they could free travelers from the grain and manure involved in horse-pulled carriages. Bicycles also emancipated women both by giving them solitary mobility and by encouraging a wider range of dress, dress that had been reserved for men in the past.

“Spreading the ‘Gospel of Good Roads,’ cyclists cajoled, leafleted and sued, and flexed their political muscles. The campaigning continued when these moneyed cyclists morphed into motorists” (2)—both as cyclists and later as motorists these individuals crusaded for better, dustless roads.

One obvious conclusion reached by this history is that cars did not nor do they now own the roads, they didn’t build the roads, and, except for freeways, they do not have exclusive rights to them. While fuel taxes subsidize roads, other taxes and duties have done plenty to promote good roads. The motorist who thinks he or she owns the road, impatient with the bicycle or pedestrian slowing down the all-important pace of life, should think twice (and read this book).

The irony of the situation is not lost on the author: to their own demise, bicyclists were too successful at promoting roads and welcoming the additional use and importance lent by the nascent automobile industry. Soon the bikes would not be welcome on their own turf. “It is perhaps ironic therefore, that cyclists were hugely responsible for popularizing what would push horses – and bicycles – off the roads” (3).

This history begins around the early 1860s and concludes around 1914 (World War I). “By 1916, the Good Roads movement was no longer led by bicycle riders, but by motorists” (1). But for the intervening years prior to 1914, those lobbying and legislating for roads had close ties to the bicycle industry. Either they were cyclists or were providing cyclists with machinery.

Many of the names we associate with the automobile industry, such as Benz, Daimler, Dunlop, and Michelin, were involved in and/or indebted to the bicycle industry. Benz, who lays claims on having invented the first car, built it on a tricycle. “The first automobile manufacturers tended to be cyclists, too: from the Dodge and Duryea brothers in America to the co-founders of Rolls-Royce and Aston Martin in Britain. At least 64 motor marques had bicycling beginnings, and in the appendix I discuss the cycle backgrounds of companies such as Cadillac, GMC and Chevrolet” (xiv).

The moral to be drawn—since this is a web log devoted to change—is that we bipeds should not be intimidated by automobiles or their alleged supremacy on the roads. Of course, one wants to avoid a direct collision, but one does not want to be cowed into obsequious submission by the automobile or the authorities being subsidized by the auto industry. While jaywalking may be a smart thing to avoid for financial and (sometimes) physical reasons, it should not be avoided on moral grounds: it is after all one more revision of history that makes the roads inaccessible to those who pollute the environment the least.

Allow me to conclude this post with Reid’s own comments on the ethics of road sharing:

Roads belong to all, a shared resource. Too often, one user – the motorised user – has been allowed to dominate. This does not require any diktats from on high. Any and every road can become a ‘motor’ way, because those piloting heavy, fast motor vehicles can use their speed and power to muscle all non-motorised users out of the way, often without knowing they’re doing it. ‘Vulnerable road users’ become either invisible, or irritants to be buzzed out of the way. Rule 170 in the [UK’s] Highway Code states: ‘Watch out for pedestrians crossing a road into which you are turning. If they have started to cross they have priority, so give way.’ Few motorists (or cyclists) know this rule exists, and pedestrians meekly scuttle out of the way, or risk being flattened. In America, the creation in the 1920s of the concept – and crime – of ‘jaywalking’ shows how roads for all users quickly became defined as roads for motorists alone. (xvi)

_____Footnotes_____

[1] Carlton Reid writes well. Although I picked up the book for its historical content (plenty of that there), his attention to language was equally as impressive. The introduction reviews many important terms—how British and American English differ (the American “sidewalk” is the British “pavement”), how words are used incorrectly (flat, square stone road surfaces are “setts” not “cobbles”), and how language betrays a groping around for accurate and elegant expression (such as “automobile,” a mixture of both Greek and Latin roots). While I read the paperback version, which is probably better for the photographs, the Kindle version would avoid the page-layout of the paperback: a single column of text so wide that tracking each line is unnecessarily difficult, perhaps the unfortunate result of the small press not having the tools to create two-column text that allows full-page-width images.

According to the author, “As much of this book is about resurrecting lost or deliberately obscured histories, there will be some who think I’ve made it all up. I’ve therefore been very careful to cite the source material for all the facts and quotes I’ve included. The copious notes would double the length of this book so I have placed them online: roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/notes” (xxiii).